Have you ever had the experience of meeting up with a dear friend for coffee or talking with your trusted therapist, and all of a sudden, you stumble into a conversation that’s a little scary and emotional? Maybe you hesitate for a minute and ask yourself if you’re gonna take the risk and really “go there”.

I don’t know about you, but when I find myself in these situations with a person I trust, and I make the choice to dive in, I end up learning a lot about myself and having an even closer relationship with the person I’m talking with.

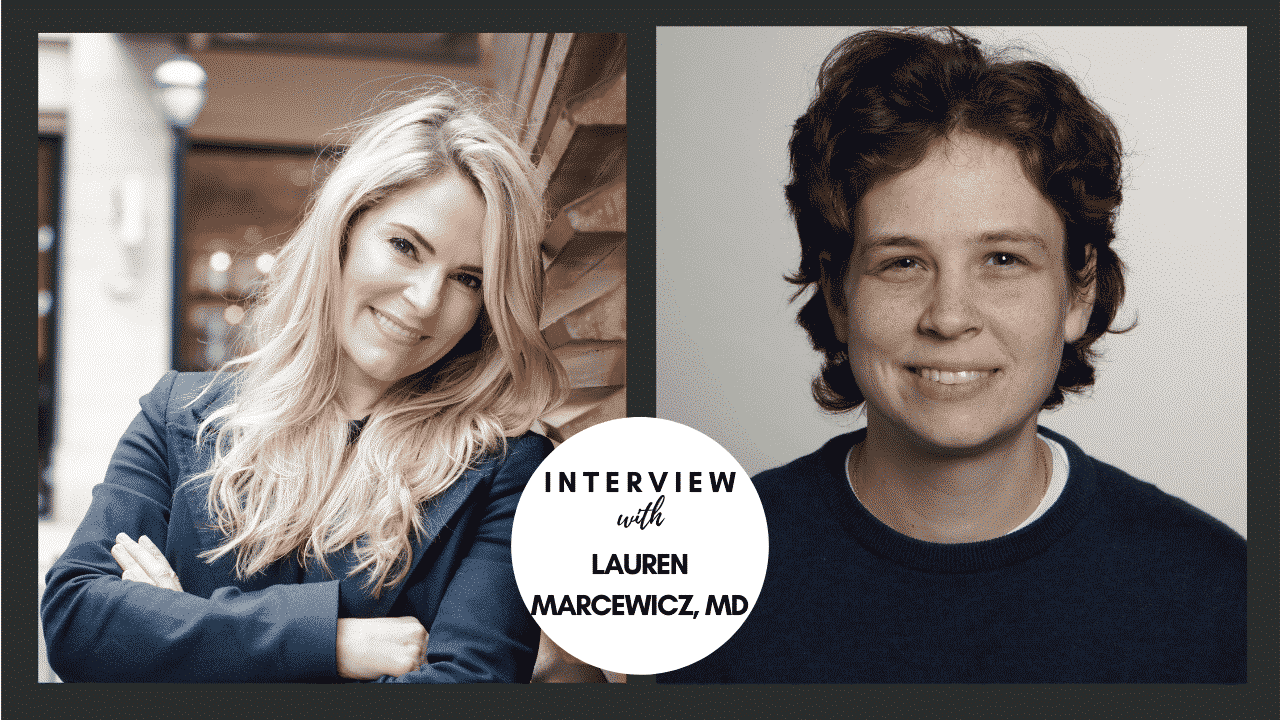

I’m going to ask you to “go there” with me today as I interview Dr. Lauren Marcewicz, Palliative Care Physician. In this interview with Dr. Marcewicz, we have a real conversation about hospice, palliative care, family dynamics, and so much more.

Here’s a peak inside my interview with Dr. Lauren Marcewicz:

- [04:49] Dr. Marcewicz shares what drew her to end of life care.

- [08:45] Learn one of Dr. Marcewicz most memorable end of life experiences.

- [14:44] Discover the difference between Palliative Care and Hospice

- [18:47] I share one of my most memorable experiences with a dying man

- [22:44] How someone qualifies for hospice care explained here

- [40:19] Active dying is a terms that many hospice and palliative care providers use. Learn what it means.

- [45:59] Tips for families starting the end of life journey from a palliative care physician.

- [50:21] Learn about the importance of anticipatory grief for the overall grieving process.

Click here to listen to the podcast

About Dr. Lauren Marcewicz

Lauren Marcewicz, MD, has been a palliative care physician at the Atlanta VA for the past 5 years. She is currently the Physician Program Lead for Palliative Care, site director for the Emory University School of Medicine Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowship, and adjunct Assistant Professor in the Division of Palliative Care, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. She also serves as a physician in the Georgia Army National Guard.

Lauren completed her residency in pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York before moving to Atlanta to study and work in epidemiology at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She completed fellowship in Hospice and Palliative Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in 2015.

Lauren currently serves on the Ethics Consultation service at the Atlanta VA Health Care System and is the facility coordinator for a national advance care planning initiative led by the VA’s National Center for Ethics in Health Care.

When Lauren is not serving in any of the above capacities, she enjoys spending time with her family, running distances that are probably a little beyond reasonable, making homemade mead, and reading comic books.